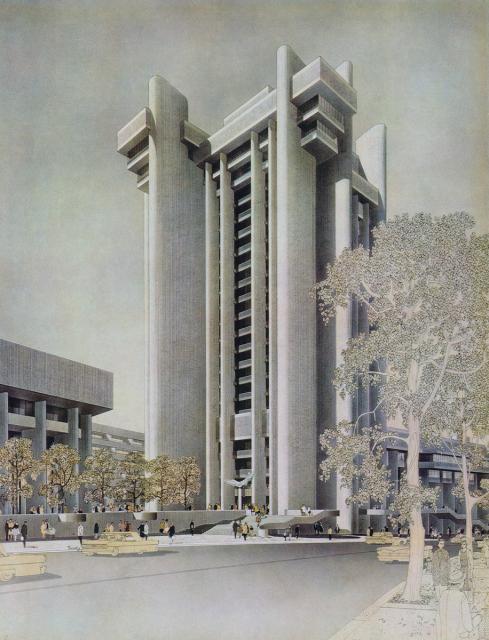

New Chardon, Merrimac and Staniford Streets, Boston, MA. Rudolph created the master plan and designed some of the buildings for this site to be developed by the State of Massachusetts (two other architectural firms took part: Shepley, Bulfinch, Richardson & Abbott and H. A. Dyer and Pedersen & Tilney). It was to be anchored by the Rudolph-designed high-rise tower which was never built. As with many of his projects, this massive undertaking began with lavish praise but has since been the subject of harsh criticism. Additionally, it is located in an area, the former West End, which was carelessly demolished in the name of urban renewal, partly for this project. The architect’s work is best displayed by the Lindemann Mental Health Center on Merrimac and Staniford Streets.

“The Boston Government Center deals with a heightening of the scale around the perimeter and a diminishing of scale at the courtyard. The perimeter at the street is large; the pedestrian interior courtyard terraces are scaled down. The use determines the scale as well as its place in the cityscape.”

Cook, John Wesley. Conversations with Architects : Philip Johnson, Kevin Roche, Paul Rudolph, Bertrand Goldberg, Morris Lapidus, Louis Kahn, Charles Moore, Robert Venturi & Denise Scott Brown. New York: Praeger, 1973.

“The generating ideas of most traditional cities are pedestrian and vehicular circulation, streets, squares, terminuses, with their space clearly defined by buildings. This means linked buildings united to form comprehensible exterior spaces. The Boston Government Service Center is the opposite of Le Corbusier’s dictum “down with the street.” It started with three separate buildings, their clients, architects and methods of financing. We didn’t build three separate buildings, as others had proposed, but one continuous building which defined the street, formed a pedestrian plaza, and utilized a multi-storied building (not yet built) to announce the development from a great distance. The scale of the lower buildings was heightened at the exterior perimeter (street) so that it read in conjunction with automobile traffic (columns 60-70 feet high plus toilet and stair cores at the corners were used). The scale at the plaza was much more intimate using stepped floors which revealed each floor level, making a bowl of space. As one approaches the stepped six-story-high building it reduces itself to only one story. Since the high-rise building is an integral part of the whole, it calls for a particular kind of high-rise building.

You would prefer to finish the project yourself?

The architect must understand the role the multi-storied building plays in the ensemble. The multi-storied building was designed as a cluster of pivoting shafts, each turning at the corners so that it leads the pedestrian into the plaza. It was not just another skyscraper. The ensemble illustrates partially the principles of a megastructure. It is multi-functional; it accepts the car by defining the space of the street plus treating the garage as an entrance to the complex; it is integrated into the surrounding fabric (at the street intersections there are small piazzas, one of Boston’s traditions). The bowl of the plaza is the counterpart of Beacon Hill and its state house one block away. It has nothing to do with stylistic elements (you could add classical details to the columns and cornices and it wouldn’t matter very much; I don’t know what could happen at the multi-storied building). When finished properly it will be “a place.””

[The building referred to as “multi-storied” and “high rise” was the Rudolph-designed tower that was never built.]

Davern, Jeanne M. “A Conversation with Paul Rudolph.” Architectural Record 170 (March 1982): 90-97.

Images of State Health, Education and Welfare Services Center